California Gold Rush

| History of California | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Timeline | |

| To 1899 | |

| Gold Rush (1848) | |

| US Civil War (1861-1865) | |

| Since 1900 | |

| Topics | |

| Maritime · Railroad · | |

| Highways · Slavery | |

| Cities | |

| Los Angeles · San Franicsco · | |

| San Diego · San Jose · | |

| Sacramento | |

|

California Portal |

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) began on January 24, 1848, when gold was discovered by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill, in Coloma, California.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag ... After 1855, California gold mining changed and is outside the 'rush' era.""The Gold Rush of California: A Bibliography of Periodical Articles". California State University, Stanislaus. 2002. http://library.csustan.edu/bsantos/goldrush/GoldTOC.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-23.</ref> News of the discovery brought some 300,000 people to California from the rest of the United States and abroad.[1] Of the 300,000, approximately half arrived by sea and half walked overland.

The gold-seekers, called "Forty-niners" (as a reference to 1849), often faced substantial hardships on the trip. While most of the newly arrived were Americans, the Gold Rush attracted tens of thousands from Latin America, Europe, Australia, and China. At first, the prospectors retrieved the gold from streams and riverbeds using simple techniques, such as panning. More sophisticated methods of gold recovery developed which were later adopted around the world. At its peak, technological advances reached a point where significant financing was required, increasing the proportion of gold companies to individual miners. Gold worth billions of today's dollars was recovered, which led to great wealth for a few. However, many returned home with little more than they had started with.

The effects of the Gold Rush were substantial. San Francisco grew from a small settlement to a boomtown, and roads, churches, schools and other towns were built throughout California. A state constitution was written and California became a state in 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850.

New methods of transportation developed as steamships came into regular service and railroads were built. Agriculture and ranching expanded throughout the state to meet the needs of the settlers. At the beginning of the Gold Rush, there was no law regarding property rights in the goldfields and a system of "staking claims" was developed. The Gold Rush also had negative effects: Native Americans were attacked and pushed off traditional lands and gold mining caused environmental harm.

Contents |

History

The Gold Rush started at Sutter's Mill, near Coloma.[2] On January 24, 1848 James W. Marshall, a foreman working for Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, found pieces of shiny metal in the tailrace of a lumber mill Marshall was building for Sutter on the American River.[3] Marshall quietly brought what he found to Sutter, and the two of them privately tested the findings. The tests showed Marshall's particles to be gold. Sutter expressed dismay: he wanted to keep the news quiet because he feared what would happen to his plans for an agricultural empire if there were a mass search for gold.[4] However, rumors soon started to spread and were confirmed in March 1848 by San Francisco newspaper publisher and merchant Samuel Brannan. The most famous quote of the California Gold Rush was by Brannan; after he had hurriedly set up a store to sell gold prospecting supplies,[5] Brannan strode through the streets of San Francisco, holding aloft a vial of gold, shouting "Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!"[6] With the news of gold, local residents in California were among the first to head for the goldfields.

At the time gold was discovered, California was part of the Mexican territory of Alta California, which was ceded to the U.S. after the end of the Mexican-American War with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848.

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first major newspaper on the East Coast to report the discovery of gold. On December 5, 1848, President James Polk confirmed the discovery of gold in an address to Congress.[7] Soon, waves of immigrants from around the world, later called the "forty-niners," invaded the Gold Country of California or "Mother Lode." As Sutter had feared, he was ruined; his workers left in search of gold, and squatters took over his land and stole his crops and cattle.[8]

San Francisco had been a tiny settlement before the rush began. When residents learned about the discovery, it at first became a ghost town of abandoned ships and businesses whose owners joined the Gold Rush,[9] but then boomed as merchants and new people arrived. The population of San Francisco exploded from perhaps 1,000[10] in 1848 to 25,000 full-time residents by 1850.[11]The sudden massive influx into a remote area overwhelmed the infrastructure. Miners lived in tents, wood shanties, or deck cabins removed from abandoned ships.[12] Wherever gold was discovered, hundreds of miners would collaborate to put up a camp and stake their claims. With names like Rough and Ready and Hangtown, each camp often had its own saloon and gambling house.[13]

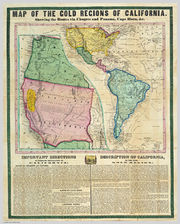

In what has been referred to as the "first world-class gold rush,"[14] there was no easy way to get to California; forty-niners faced hardship and often death on the way. At first, most Argonauts, as they were also known, traveled by sea. From the East Coast, a sailing voyage around the tip of South America would take five to eight months,[15] and cover some 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km). An alternative was to sail to the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama, to take canoes and mules for a week through the jungle, and then on the Pacific side, to wait for a ship sailing for San Francisco.[16] There was also a route across Mexico starting at Veracruz. Many gold-seekers took the overland route across the continental United States, particularly along the California Trail.[17] Each of these routes had its own deadly hazards, from shipwreck to typhoid fever and cholera.[18]

To meet the demands of the arrivals, ships bearing goods from around the world came to San Francisco as well. Ships' captains found that their crews deserted to go to the gold fields. The wharves and docks of San Francisco became a forest of masts, as hundreds of ships were abandoned. Enterprising San Franciscans turned the abandoned ships into warehouses, stores, taverns, hotels, and one into a jail.[19] Many of these ships were later destroyed and used for landfill to create more buildable land in the boomtown.

Within a few years, there was an important but lesser-known surge of prospectors into far Northern California, specifically into present-day Siskiyou, Shasta and Trinity Counties.[20] Discovery of gold nuggets at the site of present-day Yreka in 1851 brought thousands of gold-seekers up the Siskiyou Trail[21] and throughout California's northern counties.[22] Settlements of the Gold Rush era, such as Portuguese Flat on the Sacramento River, sprang into existence and then faded. The Gold Rush town of Weaverville on the Trinity River today retains the oldest continuously used Taoist temple in California, a legacy of Chinese miners who came. While there are not many Gold Rush era ghost towns still in existence, the well-preserved remains of the once-bustling town of Shasta is a California State Historic Park in Northern California.[23]

Gold was also discovered in Southern California but on a much smaller scale. The first discovery of gold, at Rancho San Francisco in the mountains north of present-day Los Angeles, had been in 1842, six years before Marshall's discovery, while California was still part of Mexico.[24] However, these first deposits, and later discoveries in Southern California mountains, attracted little notice and were of limited consequence economically.[24]

By 1850, most of the easily accessible gold had been collected, and attention turned to extracting gold from more difficult locations. Faced with gold increasingly difficult to retrieve, Americans began to drive out foreigners to get at the most accessible gold that remained. The new California State Legislature passed a foreign miners tax of twenty dollars per month, and American prospectors began organized attacks on foreign miners, particularly Latin Americans and Chinese.[25] In addition, the huge numbers of newcomers were driving Native Americans out of their traditional hunting, fishing and food-gathering areas. To protect their homes and livelihood, some Native Americans responded by attacking the miners. This provoked counter-attacks on native villages. The Native Americans, out-gunned, were often slaughtered.[26] Those who escaped massacres were many times unable to survive without access to their food-gathering areas, and they starved to death. Novelist and poet Joaquin Miller vividly captured one such attack in his semi-autobiographical work, Life Amongst the Modocs.[27]

Forty-niners

The first people to rush to the gold fields, beginning in the spring of 1848, were the residents of California themselves—primarily agriculturally oriented Americans and Europeans living in Northern California, along with Native Americans and some Californios (Spanish-speaking Californians).[28] These first miners tended to be families in which everyone helped in the effort. Women and children of all ethnicities were often found panning next to the men. Some enterprising families set up boarding houses to accommodate the influx of men; in such cases, the women often brought in steady income while their husbands searched for gold.[29]

Word of the Gold Rush spread slowly at first. The earliest gold-seekers to arrive in California during 1848 were people who lived near California, or people who heard the news from ships on the fastest sailing routes from California. The first large group of Americans to arrive were several thousand Oregonians who came down the Siskiyou Trail.[30] Next came people from The Sandwich Islands, by ship, and several thousand Latin Americans, including people from Mexico, from Peru and from as far away as Australia and Chile,[31] both by ship and overland.[32] By the end of 1848, some 6,000 Argonauts had come to California.[32] Only a small number (probably fewer than 500) traveled overland from the United States that year.[32] Some of these "forty-eighters,"[33] as the earliest gold-seekers were sometimes called, were able to collect large amounts of easily accessible gold—in some cases, thousands of dollars worth each day.[34][35] Even ordinary prospectors averaged daily gold finds worth 10 to 15 times the daily wage of a laborer on the East Coast. A person could work for six months in the goldfields and find the equivalent of six years' wages back home.[36] Some hoped to get rich quick and return home, and others wished to start businesses in California.

By the beginning of 1849, word of the Gold Rush had spread around the world, and an overwhelming number of gold-seekers and merchants began to arrive from virtually every continent. The largest group of forty-niners in 1849 were Americans, arriving by the tens of thousands overland across the continent and along various sailing routes[37] (the name "forty-niner" was derived from the year 1849). Many came by way of the Isthmus of Panama and the steamships of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Australians[38] and New Zealanders picked up the news from ships carrying Hawaiian newspapers, and thousands, infected with "gold fever," boarded ships for California.[39] Forty-niners came from Latin America, particularly from the Mexican mining districts near Sonora.[39] Gold-seekers and merchants from Asia, primarily from China,[40] began arriving in 1849, at first in modest numbers to Gum San ("Gold Mountain"), the name given to California in Chinese.[41] The first immigrants from Europe, reeling from the effects of the Revolutions of 1848 and with a longer distance to travel, began arriving in late 1849, mostly from France,[42] with some Germans, Italians, and Britons.[37] Most of these national groups arrived from seafaring, coastal regions.

It is estimated that approximately 90,000 people arrived in California in 1849—about half by land and half by sea.[43] Of these, perhaps 50,000 to 60,000 were Americans, and the rest were from other countries.[37] By 1855, it is estimated at least 300,000 gold-seekers, merchants, and other immigrants had arrived in California from around the world.[44] The largest group continued to be Americans, but there were tens of thousands each of Mexicans, Chinese, Britons, and Australians [45] French, and Latin Americans,[46] together with many smaller groups of miners, such as Filipinos, Basques[47] and Turks.[48] People from small villages in the hills near Genova, Italy were among the first to settle permanently in the Sierra foothills; they brought with them traditional agricultural skills, developed to survive cold winters.[49] A modest number of miners of African ancestry (probably less than 4,000)[50] had come from the Southern States,[51] the Caribbean and Brazil.[52]

A notable number of immigrants were from China. Several hundred Chinese arrived in California in 1849 and 1850, and in 1852 more than 20,000 landed in San Francisco.[53] Their distinctive dress and appearance was highly recognizable in the gold fields, and created a degree of animosity towards the Chinese.[53]

There were also many women in the Gold Rush. They held various roles including prostitutes, single entrepreneurs, married women, poor and wealthy women. They also were of various ethnicities including Anglo-American, Hispanic, Native, European, Chinese. The reasons they came varied: some came with their husbands, refusing to be left behind to fend for themselves, some came because their husbands sent for them, and others came (singles and widows) for the adventure and economic opportunities.[54] On the trail many people died from accidents, cholera, fever, and myriad other causes, and many women became widows before even setting eyes on California. While in California, women were widows quite frequently due to mining accidents, disease, or mining disputes of their husbands. Life in the gold fields offered opportunities for women to break from their traditional work.[55]

Legal rights

When the Gold Rush began, California was a peculiarly lawless place. On the day when gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill, California was still technically part of Mexico, under American military occupation as the result of the Mexican-American War. With the signing of the treaty ending the war on February 2, 1848, California became a possession of the United States, but it was not a formal "territory" and did not become a state until September 9, 1850. California existed in the unusual condition of a region under military control. There was no civil legislature, executive or judicial body for the entire region.[56] Local residents operated under a confusing and changing mixture of Mexican rules, American principles, and personal dictates.

While the treaty ending the Mexican-American War obliged the United States to honor Mexican land grants,[57] almost all the goldfields were outside those grants. Instead, the goldfields were primarily on "public land", meaning land formally owned by the United States government.[58] However, there were no legal rules yet in place, and no practical enforcement mechanisms.[59]

The benefit to the forty-niners was that the gold was simply "free for the taking" at first. In the goldfields at the beginning, there was no private property, no licensing fees, and no taxes.[60][61] The miners essentially adapted Mexican mining law existing in California.[62] For example, the rules attempted to balance the rights of early arrivers at a site with later arrivers; a "claim" could be "staked" by a prospector, but that claim was valid only as long as it was being actively worked.[63][64] Miners worked at a claim only long enough to determine its potential. If a claim was deemed as low-value—as most were—miners would abandon the site in search for a better one. In the case where a claim was abandoned or not worked upon, other miners would "claim-jump" the land. "Claim-jumping" meant that a miner began work on a previously claimed site.[63][64] Disputes were sometimes handled personally and violently, and were sometimes addressed by groups of prospectors acting as arbitrators.[58][63][64] This often led to heightened ethnic tensions.[65]

Development of gold recovery techniques

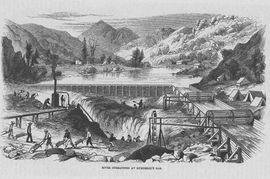

Because the gold in the California gravel beds was so richly concentrated, the early forty-niners simply panned for gold in California's rivers and streams, a form of placer mining.[66] However, panning cannot be done on a large scale, and industrious miners and groups of miners graduated to placer mining "cradles" and "rockers" or "long-toms"[67] to process larger volumes of gravel.[68] In the most complex placer mining, groups of prospectors would divert the water from an entire river into a sluice alongside the river, and then dig for gold in the newly exposed river bottom.[69] Modern estimates by the U.S. Geological Survey are that some 12 million ounces[70] (370 t) of gold were removed in the first five years of the Gold Rush (worth approximately US$7 billion at November 2006 prices).[71]

In the next stage, by 1853, hydraulic mining was used on ancient gold-bearing gravel beds that were on hillsides and bluffs in the gold fields.[72] In a modern style of hydraulic mining first developed in California, a high-pressure hose directed a powerful stream or jet of water at gold-bearing gravel beds.[73] The loosened gravel and gold would then pass over sluices, with the gold settling to the bottom where it was collected. By the mid-1880s, it is estimated that 11 million ounces (340 t) of gold (worth approximately US$6.6 billion at November 2006 prices) had been recovered by "hydraulicking."[71] This style of hydraulic mining later spread around the world. An alternative to "hydraulicking" was "coyoteing."[74] This method involved digging a shaft 6 to 13 meters (20 to 40 feet) deep into bedrock along the shore of a stream. Tunnels were then dug in all directions to reach the richest veins of pay dirt.

A byproduct of these extraction methods was that large amounts of gravel, silt, heavy metals, and other pollutants went into streams and rivers.[75] Many areas still bear the scars of hydraulic mining since the resulting exposed earth and downstream gravel deposits are unable to support plant life.[76]

After the Gold Rush had concluded, gold recovery operations continued. The final stage to recover loose gold was to prospect for gold that had slowly washed down into the flat river bottoms and sandbars of California's Central Valley and other gold-bearing areas of California (such as Scott Valley in Siskiyou County). By the late 1890s, dredging technology (which was also invented in California) had become economical,[77] and it is estimated that more than 20 million ounces (620 t) were recovered by dredging (worth approximately US$12 billion at November 2006 prices).[71]

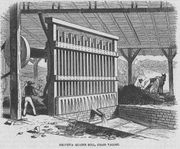

Both during the Gold Rush and in the decades that followed, gold-seekers also engaged in "hard-rock" mining, that is, extracting the gold directly from the rock that contained it (typically quartz), usually by digging and blasting to follow and remove veins of the gold-bearing quartz.[78] Once the gold-bearing rocks were brought to the surface, the rocks were crushed, and the gold was separated out (using moving water), or leached out, typically by using arsenic or mercury (another source of environmental contamination).[79] Eventually, hard-rock mining wound up being the single largest source of gold produced in the Gold Country.[71][80]

Profits

Recent scholarship confirms that merchants made far more money than miners during the Gold Rush.[81][82] The wealthiest man in California during the early years of the Gold Rush was Samuel Brannan, the tireless self-promoter, shopkeeper and newspaper publisher.[83] Brannan opened the first supply stores in Sacramento, Coloma, and other spots in the gold fields. Just as the Gold Rush began, he purchased all the prospecting supplies available in San Francisco and re-sold them at a substantial profit.[83] However, substantial money was made by some gold-seekers as well. For example, within a few months, one small group of prospectors, working on the Feather River in 1848, retrieved a sum of gold worth more than $1.5 million by 2006 prices.[84]

On average, half the gold-seekers made a modest profit, after all expenses were taken into account. Most, however, especially those arriving later, made little or wound up losing money.[85] Similarly, many unlucky merchants set up in settlements that disappeared, or were wiped out in one of the calamitous fires that swept the towns springing up. By contrast, a businessman who went on to great success was Levi Strauss, who first began selling denim overalls in San Francisco in 1853.[86] Other businessmen, through good fortune and hard work, reaped great rewards in retail, shipping, entertainment, lodging,[87] or transportation.[88] Boardinghouses, food preparation, sewing, and laundry were highly profitable businesses often run by women (married, single, or widowed) who realized men would pay well for a service done by a woman. Brothels also brought in large profits, especially when combined with saloons and gaming houses.[89]

By 1855, the economic climate had changed dramatically. Gold could be retrieved profitably from the goldfields only by medium to large groups of workers, either in partnerships or as employees. By the mid-1850s, it was the owners of these gold-mining companies who made the money. Also, the population and economy of California had become large and diverse enough that money could be made in a wide variety of conventional businesses.[90]

Path of the gold

Once the gold was recovered, there were many paths the gold itself took. First, much of the gold was used locally to purchase food, supplies and lodging for the miners. It also went towards entertainment, which consisted of anything from a traveling theater to alcohol, gambling, and prostitutes. These transactions often took place using the recently recovered gold, carefully weighed out.[91] These merchants and vendors, in turn, used the gold to purchase supplies from ship captains or packers bringing goods to California.[92] The gold then left California aboard ships or mules to go to the makers of the goods from around the world. A second path was the Argonauts themselves who, having personally acquired a sufficient amount, sent the gold home, or returned home taking with them their hard-earned "diggings." For example, one estimate is that some US$80 million worth of California gold was sent to France by French prospectors and merchants.[93] As the Gold Rush progressed, local banks and gold dealers issued "banknotes" or "drafts"—locally accepted paper currency—in exchange for gold,[94] and private mints created private gold coins.[95] With the building of the San Francisco Mint in 1854, gold bullion was turned into official United States gold coins for circulation.[96] The gold was also later sent by California banks to U.S. national banks in exchange for national paper currency to be used in the booming California economy.[97]

Effects

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of new people within a few years, compared to a population of some 15,000 Europeans and Californios beforehand,[98] had many dramatic effects.[99]

Development of government and commerce

The Gold Rush propelled California from a sleepy, little-known backwater to a center of the global imagination and the destination of hundreds of thousands of people. The new immigrants often showed remarkable inventiveness and civic-mindedness. For example, in the midst of the Gold Rush, towns and cities were chartered, a state constitutional convention was convened, a state constitution written, elections held, and representatives sent to Washington, D.C. to negotiate the admission of California as a state.[100] Large-scale agriculture (California's second "Gold Rush"[101]) began during this time.[102] Roads, schools, churches,[103] and civic organizations quickly came into existence.[100] The vast majority of the immigrants were Americans. Pressure grew for better communications and political connections to the rest of the United States, leading to statehood for California on September 9, 1850, in the Compromise of 1850 as the 31st state of the United States.

Between 1847 and 1870, the population of San Francisco increased from 500 to 150,000.[104] The Gold Rush wealth and population increase led to significantly improved transportation between California and the East Coast. The Panama Railway, spanning the Isthmus of Panama, was finished in 1855.[105] Steamships, including those owned by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, began regular service from San Francisco to Panama, where passengers, goods and mail would take the train across the Isthmus and board steamships headed to the East Coast. One ill-fated journey, that of the S.S. Central America,[106] ended in disaster as the ship sank in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas in 1857, with approximately three tons of California gold aboard.[107][108]

Effects on Native Americans

The human and environmental costs of the Gold Rush were substantial. Native Americans, dependent on traditional hunting and gathering, became the victims of starvation and disease, as gravel, silt and toxic chemicals from prospecting operations killed fish and destroyed habitats.[75][76] The surge in the mining population also resulted in the disappearance of game and food gathering locales as gold camps and other settlements were built amidst them. Later farming spread to supply the camps, taking more land from the use of Native Americans. Starvation often provoked the Native tribes to steal or take by force food and livestock from the miners, increasing miner hostility and provoking retaliation against them.

Native Americans succumbed to smallpox, influenza and measles in large numbers. Some estimates indicate case fatality rates of 80-90 % in Native American populations during smallpox epidemics.[109]

The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians,[110] passed on April 22, 1850 by the California Legislature, allowed settlers to continue the Californio practice of capturing and using Native people as bonded workers. It also provided the basis for the enslavement and trafficking in Native American labor, particularly that of young women and children, which was carried on as a legal business enterprise. Native American villages were regularly raided to supply the demand, and young women and children were carried off to be sold, the men and remaining people often being killed in genocidal attacks.[111]

From a pre-European population estimated at 310,000 which had been decimated by Spanish Colonization and colonial mission practices, including diseases carried by the European settlers, the Gold Rush turned into a virtual "reign of terror" for tribesmen in or near mining districts.[112] Despite resistance in various conflicts, the Native American population in California, estimated at 150,000 in 1845, was less than 30,000 by 1870.[113] It is estimated that some 4,500 Native Americans suffered violent deaths between 1849 and 1870.[114]

Anti-foreigner laws

After the initial boom was ending, explicitly anti-foreign and racist attacks, laws and confiscatory taxes sought to drive out foreigners from the mines, but especially the Chinese and Latin American immigrants mostly from Sonora, Mexico and Chile.[53][115] The toll on the American immigrants could be severe as well: one in twelve forty-niners perished, as the death and crime rates during the Gold Rush were extraordinarily high, and the resulting vigilantism also took its toll.[116]

World-wide economic stimulation

The Gold Rush stimulated economies around the world as well. Farmers in Chile, Australia, and Hawaii found a huge new market for their food; British manufactured goods were in high demand; clothing and even prefabricated houses arrived from China.[117] The return of large amounts of California gold to pay for these goods raised prices and stimulated investment and the creation of jobs around the world.[118] Australian prospector, Edward Hargraves, noting similarities between the geography of California and his home, returned to Australia to discover gold and spark the Australian gold rushes.[119]

Within a few years after the end of the Gold Rush, in 1863, the groundbreaking ceremony for the western leg of the First Transcontinental Railroad was held in Sacramento. The line's completion, some six years later, financed in part with Gold Rush money,[120] united California with the central and eastern United States. Travel that had taken weeks or even months could now be accomplished in days.[121]

Image and memory

California's name became indelibly connected with the Gold Rush, and fast success in a new world became known as the "California Dream."[122] California was perceived as a place of new beginnings, where great wealth could reward hard work and good luck. Historian H. W. Brands noted that in the years after the Gold Rush, the California Dream spread across the nation:

| “ | "The old American Dream . . . was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin's "Poor Richard" . . . of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream . . . became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter's Mill."[123] | ” |

Overnight California gained the international reputation as the "golden state"--with gold and lawlessness the main themes.[124] The literary history of the Gold Rush is reflected in the works of Mark Twain (The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County), Bret Harte (A Millionaire of Rough-and-Ready), Joaquin Miller (Life Amongst the Modocs), and many others.[27][125]

Included among the modern legacies of the California Gold Rush are the California state motto, "Eureka" ("I have found it"), Gold Rush images on the California State Seal,[126] and the state nickname, "The Golden State," as well as place names, such as Placer County, Rough and Ready, Placerville (formerly named "Dry Diggings" and then "Hangtown" during rush time), Whiskeytown, Drytown, Angels Camp, Happy Camp, and Sawyer's Bar. The San Francisco 49ers National Football League team, and the similarly named athletic teams of California State University, Long Beach, are named for the prospectors of the California Gold Rush.

Today, aptly named State Route 49 travels through the Sierra Nevada foothills, connecting many Gold Rush-era towns such as Placerville, Auburn, Grass Valley, Nevada City, Coloma, Jackson, and Sonora.[127] This state highway also passes very near Columbia State Historic Park, a protected area encompassing the historic business district of the town of Columbia; the park has preserved many Gold Rush-era buildings, which are presently occupied by tourist-oriented businesses.

Geology

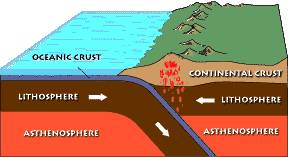

Global forces operating over hundreds of millions of years resulted in the large concentration of gold in California. Only gold that is concentrated can be economically recovered. Some 400 million years ago, California lay at the bottom of a large sea; underwater volcanoes deposited lava and minerals (including gold) onto the sea floor. Beginning about 200 million years ago, tectonic pressure forced the sea floor beneath the American continental mass.[128] As it sank, or subducted, below today's California, the sea floor melted into very large molten masses (magma). This hot magma forced its way upward under what is now California, cooling as it rose,[129] and as it solidified, veins of gold formed within fields of quartz.[129][130] These minerals and rocks came to the surface of the Sierra Nevada,[131] and eroded. The exposed gold was carried downstream by water and gathered in quiet gravel beds along the sides of old rivers and streams.[132] The forty-niners first focused their efforts on these deposits of gold, which had been gathered in the gravel beds by hundreds of millions of years of geologic action.[133][134]

See also

California Gold Rush

- Category:People of the California Gold Rush

- List of people associated with the California Gold Rush

- Women in the California Gold Rush

- Bodie, California Historic State Park

Songs

- Oh! Susanna

- Oh My Darling, Clementine

- Hamborger Veermaster

- Mursheen Durkin

California

- History of the west coast of North America

- History of California to 1899

U.S. gold rushes

- Carolina Gold Rush (1799)

- Virginia gold mining (beginning 1804)

- Georgia Gold Rush (beginning 1829)

- Pike's Peak Gold Rush (1858–1860)

- Holcomb Valley gold rush (1860s)

- Black Hills Gold Rush (Dakota) (1874)

- Fairbanks Gold Rush (1902–1905)

Early U.S. mining

- Comstock Lode, first major silver mining in the U.S.

- Copper mining in Michigan, first major copper mining in the U.S.

Notes

- ↑ "California Gold Rush, 1848-1864". Learn California.org, a site designed for the California Secretary of State. http://www.learncalifornia.org/doc.asp?id=118. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ For a detailed map, see California Historic Gold Mines, published by the State of California. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888). History of California, Volume 23: 1848–1859. San Francisco: The History Company. pp. 32–34. http://www.1st-hand-history.org/Hhb/23/album1.html.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches; gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. p. 60.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005). California: a history. New York: The Modern Library. p. 80.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 51 ("800 residents").

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California (California History Sesquicentennial Series, 2). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 187.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 126.

- ↑ "A Golden Dream? A Look at Mining Communities in the 1849 Gold Rush". Sell-oldgold.com, an educational resource for historical gold, silver, and coin information. http://www.sell-oldgold.com/articles/Mining-Communities-in-the-1849-Gold-Rush.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), p. 1.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Anchor (reprint ed.). pp. 103–121.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 75–85. Another route across Nicaragua was developed in 1851; it was not as popular as the Panama option. Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 252–253.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 5.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999), pp. 101, 107.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80; "Shipping is the Foundation of San Francisco — Literally". Oakland Museum of California. 1998. http://www.museumca.org/goldrush/getin-pr01.html. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 363–366.

- ↑ Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail. New York: McGraw Hill.pp. 361–362.

- ↑ Wells, Harry L. (1881). History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland, California: D.J. Stewart & Co.. pp. 60–64.

- ↑ The buildings of Bodie, the best-known ghost town in California, date from the 1870s and later, well after the end of the Gold Rush.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (1999), p. 3.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 9.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 8.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Miller, Joaquin (1873). Life amongst the Modocs: unwritten history. Berkeley: Heyday Books; reprint edition (January 1996). On-line version of book

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 43–46.

- ↑ Moynihan, Ruth B., Armitage, Susan, and Dichamp, Christiane Fischer (eds.) (1990). So Much to Be Done. Lincoln: U Nebraska, p. 3

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000). Rooted in barbarous soil: people, culture, and community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press. pp. 50–54.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 48–53.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 50–54.

- ↑ Caughey, John Walton (1975). The California Gold Rush. University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 0520027639. http://books.google.com/?id=CLMJ1oLlhXQC&pg=PA17. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 197–202.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999) p. 63. Holliday notes these luckiest prospectors were recovering, in short amounts of time, gold worth in excess of $1 million when valued at the dollars of today.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 28.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 57–61.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 53–61.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 53–56.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 61–64.

- ↑ Magagnini, Stephen (January 18, 1998)"Chinese transformed 'Gold Mountain'", The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 93–103.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 57–61. Other estimates range from 70,000 to 90,000 arrivals during 1849 (ibid. p. 57).

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 25.

- ↑ Exploration and Settlement (John Bull and Uncle Sam)

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 62.

- ↑ Gold Rush: Background

- ↑ Freguli, Carolyn. (eds.) (2008), pp.8–9.

- ↑ Another estimate is 2,500 forty-niners of African ancestry. Rawls, James, J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 5.

- ↑ African Americans who were slaves and came to California during the Gold Rush could gain their freedom. One of the miners was African American Edmond Edward Wysinger (1816-1891), see also Moses Rodgers (1835-1900)

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 67–69.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Out of Many, 5th Edition Volume 1, Faragher 2006 (p.411)

- ↑ Moynihan, Ruth B., Armitage, Susan, and Dichamp, Christiane Fischer (eds.) (1990), pp. 3-8

- ↑ Levy, Joann (1992). They saw the elephant: Women in the California Gold Rush. Archon:N.p., pp. xxii, 92

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999), pp. 115–123.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 235.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p.127. There were fewer than 1,000 U.S. soldiers in California at the beginning of the Gold Rush.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 27.

- ↑ The federal law in place at the time of the California Gold Rush was the Preemption Act of 1841, which allowed "squatters" to improve federal land, then buy it from the government after 14 months.

- ↑ Paul, Rodman W. (1947) California Gold, Lincoln: Univ. Nebraska Press, p.211–213.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Clay, Karen and Wright, Gavin. (2005), pp. 155–183.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Clappe, Louise Amelia Knapp Smith (ed. 2001). The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, 1851-1852. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California. p. 109. ISBN 1890771007. http://books.google.com/?id=lQ6ekLo9SHEC&dq=dame%20shirley&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q. Retrieved July 31, 2010. “Dame Shirley” was the name adopted by Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe as she wrote a series of letters to her family describing in detail her life in the Feather River goldfields. The letters were originally published in 1854-1855 by The Pioneer magazine.

- ↑ The rules of mining claims adopted by the forty-niners spread with each new mining rush throughout the western United States. The U.S. Congress finally legalized the practice in the "Chaffee laws" of 1866 and the "placer law" of 1870. Lindley, Curtis H. (1914) A Treatise on the American Law Relating to Mines and Mineral Lands, San Francisco: Bancroft-Whitney, p.89–92. Karen Clay and Gavin Wright, "Order Without Law? Property Rights During the California Gold Rush." Explorations in Economic History 2005 42(2): 155-183. See also John F. Burns, and Richard J. Orsi, eds; Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California University of California Press, 2003

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 198–200.

- ↑ Images and detailed description of placer mining tools and techniques; image of a long tom

- ↑ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1888), pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 90.

- ↑ The Troy weight system is traditionally used to measure precious metals, not the more familiar avoirdupois weight system. The term "ounces" used in this article to refer to gold typically refers to troy ounces. There are some historical uses where, because of the age of the use, the intention is ambiguous.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 Mining History and Geology of the Mother Lode (accessed Oct. 16, 2006).

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 89.

- ↑ Use of volumes of water in large-scale gold-mining dates at least to the time of the Roman Empire. Roman engineers built extensive aqueducts and reservoirs above gold-bearing areas, and released the stored water in a flood so as to remove over-burden and expose gold-bearing bedrock, a process known as hushing. The bedrock was then attacked using fire and mechanical means, and volumes of water were used again to remove debris, and to process the resulting ore. Examples of this Roman mining technology may be found at Las Médulas in Spain and Dolaucothi in South Wales. The gold recovered using these methods was used to finance the expansion of the Roman Empire. Hushing was also used in lead and tin mining in Northern Britain and Cornwall. There is, however, no evidence of the earlier use of hoses, nozzles and continuous jets of water in the manner developed in California during the Gold Rush.

- ↑ "Gold Mining Techniques of the Gold Rush of 1849". Refinity.com, a resource for gold, silver, and coin information. http://refinity.com/media/Gold-Mining-Techniques-of-the-Gold-Rush-of-1849.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 32–36.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 116–121.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 199.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 36–39.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 39–43.

- ↑ Charles N. Alpers, Michael P. Hunerlach, Jason T. May, and Roger L. Hothem. "Mercury Contamination from Historical Gold Mining in California". U.S. Geological Survey. http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2005/3014/. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Karen Clay and Randall Jones, "Migrating to Riches? Evidence from the California Gold Rush," Journal of Economic History, Dec 2008, Vol. 68 Issue 4, pp 997-1027

- ↑ Rohrbough, Malcolm J. (1998). Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21659-8.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Holliday, J. S. (1999) pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999), p. 63.

- ↑ Clay and Jones, "Migrating to Riches? Evidence from the California Gold Rush," Journal of Economic History, 2008,

- ↑ The famous Levi's jeans were not invented until the 1870s. Lynn Downey, Levi Strauss & Co. (2007)

- ↑ James Lick made a fortune running a hotel and engaging in land speculation in San Francisco. Lick's fortune was used to build Lick Observatory.

- ↑ Four particularly successful Gold Rush era merchants were Leland Stanford, Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, Sacramento area businessmen (later known as the Big Four) who financed the western leg of the First Transcontinental Railroad, and became very wealthy as a result.

- ↑ Susan Lee Johnson, Roaring Camp: The social world of the California Gold Rush. (2000), pp. 164-168.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 52-68, 193–197.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 212–214.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 256–259.

- ↑ Holliday, J. S. (1999) p. 90.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 193–197; 214–215.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 214.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), p. 212.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), p. 50. Other estimates are that there were 7,000–13,000 non-Native Americans in California before January 1848. See Holliday, J. S. (1999), pp. 26, 51.

- ↑ Historians have reflected on the Gold Rush and its effect on California. Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft used the phrase that the Gold Rush advanced California into a "rapid, monstrous maturity," and historian Kevin Starr stated, for all its problems and benefits, the Gold Rush established the "founding patterns, the DNA code, of American California." See Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 80.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 91–93.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 243–248. By 1860, California had over 200 flour mills, and was exporting wheat and flour around the world. Ibid. at 278–280.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California dream: 1850–1915. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–75.

- ↑ Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1870, U.S. Bureau of the Census

- ↑ Harper's New Monthly Magazine March 1855, Volume 10, Issue 58, p. 543.

- ↑ S.S. Central America information; Final voyage of the S.S. Central America. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 192–196.

- ↑ Another notable ship wreck was the steamship Winfield Scott, bound to Panama from San Francisco, which crashed into Anacapa Island off the Southern California coast in December 1853. All hands and passengers were saved, along with the cargo of gold, but the ship was a total loss.

- ↑ "The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology". Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). Cambridge University Press. p.205. ISBN 0-521-55203-6

- ↑ "An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians". http://www.indiancanyon.org/ACTof1850.html.

- ↑ Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: Univ. of Nebraska Press. p. 243.

- ↑ Castillo, Edward D. (1998). "California Indian History". http://www.nahc.ca.gov/califindian.html. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005), p. 99.

- ↑ "Minorities During the Gold Rush". California Secretary of State. http://www.learncalifornia.org/doc.asp?id=1933. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin and Orsi, Richard J. (eds.) (2000), pp. 56–79.

- ↑ Starr, Kevin (2005), pp. 84–87. Joaquin Murrieta was a famous Mexican bandit during the Gold Rush of the 1850s.The Last of the California Rangers (1928), “16. California Banditti,” by Jill L. Cossley-Batt

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 285–286.

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 287–289.

- ↑ Younger, R.M. 'Wondrous Gold' in Australia and the Australians: A New Concise History, Rigby, Sydney, 1970

- ↑ Rawls, James J. and Orsi, Richard (eds.) (1999), pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Historians James Rawls and Walton Bean have postulated that were it not for the discovery of gold, Oregon might have been granted statehood ahead of California, and therefore the first "Pacific Railroad might have been built to that state." See Rawls, James, J., and Walton Bean (2003), p. 112.

- ↑ Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (1986)

- ↑ Brands, H.W. (2003), p. 442.

- ↑ Robert A. Burchell, "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875," California Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer I974): 115-30, shows that stories about Gold Rush lawlessness deterred immigration for two decades.

- ↑ Watson (2005) looks at Bret Harte's notion of Western partnership in such California gold rush stories as "The Luck of Roaring Camp` (1868), "Tennessee's Partner" (1869), and "Miggles" (1869). While critics have long recognized Harte's interest in gender constructs, Harte's depictions of Western partnerships also explore changing dynamics of economic relationships and gendered relationships through terms of contract, mutual support, and the bonds of labor. Matthew A. Watson, "The Argonauts of '49: Class, Gender, and Partnership in Bret Harte's West." Western American Literature 2005 40(1): 33-53.

- ↑ Gold Rush images on the state seal include a forty-niner digging with a pick and shovel, a pan for panning gold, and a "long-tom." In addition, the ships on the water suggest the sailing ships filling the Sacramento River and San Francisco Bay during the Gold Rush era.

- ↑ "Your guide to the Mother Lode:Complete map of historic Hwy 49.". historichwy49.com. http://www.historichwy49.com/mainmap.html. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 168–169.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Brands, H.W. (2003), pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 174–178.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 169–173.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 94–100.

- ↑ Hill, Mary (1999), pp. 105–110.

- ↑ Curiously, there were decades of minor earthquakes - more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California - before the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Widely previously interpreted as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake they have been found to have a strong seasonal pattern and were found to be due to large seasonal sediment loads in coastal bays that overlie faults as a result of mining of gold inland. Seasonal Seismicity of Northern California Before the Great 1906 Earthquake, (Journal) Pure and Applied Geophysics, ISSN 0033-4553 (Print) 1420-9136 (Online), volume 159, Numbers 1-3 / January, 2002, Pages 7-62.

References

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1884–1890) History of California, vols. 18–24.

- Brands, H.W. (2003). The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0385720885.

- Clappe, Louise Amelia Knapp Smith (ed. 2001). The Shirley Letters from the California Mines, 1851-1852. Heyday Books, Berkeley, California. p. 109. ISBN 1890771007. http://books.google.com/?id=lQ6ekLo9SHEC&dq=dame%20shirley&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- Clay, Karen; Gavin Wright (April 2005). "Order Without Law? Property Rights During the California Gold Rush". Explorations in Economic History 42 (2): 155–183. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2004.05.003.

- Dillon, Richard (1975). Siskiyou Trail: the Hudson's Bay Company route to California. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-016980-2.

- Gaither, Chris; Chmielewski, Dawn C. (2006-10-10). "Google Bets Big on Videos" (PDF). Los Angeles Times. http://msl1.mit.edu/furdlog/docs/latimes/2006-10-10_latimes_google_youtube.pdf. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- Harper's New Monthly Magazine March 1855, volume 10, issue 58, p. 543, complete text online.

- Heizer, Robert F. (1974). The destruction of California Indians. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7262-6.

- Hill, Mary (1999). Gold: the California story. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21547-8.

- Holliday, J. S. (1999). Rush for riches: Gold fever and the making of California. Oakland, California, Berkeley and Los Angeles: Oakland Museum of California and University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21401-3.

- Johnson, Susan Lee (2001). Roaring Camp: the social world of the California Gold Rush. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32099-5.

- Levy, JoAnn (1992) [1990]. They saw the elephant: women in the California Gold Rush. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2473-3.

- Miller, Joaquin (1873). Life amongst the Modocs: unwritten history. Berkeley: Heyday Books; reprint edition (January 1996). ISBN 0-930588-79-7.

- Moynihan, Ruth B.; Armitage, Susan, and Dichamp, Christiane Fischer (eds.) (1990). So much to be done: Women settlers on the mining and ranching frontier, 2d ed. (Women in the West). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803282486.

- Rawls, James, J.; Bean, Walton (2003). California: An interpretive history. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-255255-7.

- Rawls, James, J. and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California. California History Sesquicentennial, 2. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21771-3.

- Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California dream: 1850–1915. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504233-6.

- Starr, Kevin (2005). California: a history. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64240-4.

- Starr, Kevin and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (2000). Rooted in barbarous soil: people, culture, and community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22496-5.

- Wells, Harry L. (1971) [1881]. History of Siskiyou County, California. Siskiyou Historical Society. ASIN B0006YP8IE, OCLC 6150902.

Further reading

- Burchell, Robert A. (Summer 1974). "The Loss of a Reputation; or, The Image of California in Britain before 1875". California Historical Quarterly 53 (3): 115–130. ISSN 0097-6059.

- Burns, John F. and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (2003). Taming the Elephant: Politics, Government, and Law in Pioneer California. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23413-8. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105960680. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- Drager, K.; C. Fracchia (1997). The Golden Dream: California from Gold Rush to Statehood. Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Center Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55868-312-7.

- Dwyer, Richard A.; Richard E. Lingenfelter, David Cohen (1964). The Songs of the Gold Rush. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Eifler, Mark A. (2002). Gold Rush Capitalists: Greed and Growth in Sacramento. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2822-9.

- Hart, Eugene (2003). A Guide to the California Gold Rush. Merced: Freewheel Publications. ISBN 0-9634197-2-2.

- Helper, Hinton Rowan (1855). The Land of Gold: Reality Versus Fiction. Baltimore: H. Taylor. http://books.google.com/?id=swQNAAAAIAAJ.

- Holliday, J. S.; William Swain (2002) [1981]. The World Rushed in: The California Gold Rush Experience. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3464-X.

- Hurtado, Albert L. (2006). John Sutter: A Life on the North American Frontier. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3772-X.

- Klare, Normand E. (2005). The Final Voyage of the SS Central America 1857. Ashland, Oregon: Klare Taylor Publishers. ISBN 0-97644-03-0-X.

- Knorr, Lawrence (2008). A Pennsylvania Mennonite and the California Gold Rush. Camp Hill: Sunbury Press. ISBN 0-9760925-8-1.

- Owens, Kenneth N. (ed.) (2002). Riches for All: The California Gold Rush and the World. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8617-1.

- Roberts, Brian (2000). American Alchemy: The California Gold Rush and Middle-class Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4856-5.

- Rohrbough, Malcolm J. (1998). Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21659-8.

- Watson, Matthew A. (2005). "The Argonauts of '49: Class, Gender, and Partnership in Bret Harte's West.". Western American Literature 40 (1): 33–53. ISSN 0043-3462.

External links

- California Gold Rush at the Open Directory Project

- California Gold Rush at PBS

- Gold Rush! at the Oakland Museum of California

- Museum of the Siskiyou Trail

- California Gold Rush chronology at The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- Description by John Sutter of the Discovery of Gold at The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park

- Columbia State Historic Park

- Weaverville State Historic Park

- Shasta State Historic Park

- Impact of Gold Rush on California at The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco

- California Gold Rush timeline

- Gold Rush geology

- Gold at the website of United States Geological Survey

- Gold Rush era ship wreck at the National Park Service

- Stories of the People who lived the California Gold Rush

- Historic Maps of the California Gold Rush at David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

- Gold Country Museum in Placer County, California

- "California as I Saw It:" First-Person Narratives of California's Early Years, 1849-1900 Library of Congress American Memory Project

|

||||||||||||||